LLVM Cycle Terminology¶

Cycles¶

Cycles are a generalization of LLVM loops, defined recursively as follows [HavlakCycles]:

In a directed graph G, an outermost cycle is a maximal strongly connected region with at least one internal edge. (Informational note — The requirement for at least one internal edge ensures that a single basic block is a cycle only if there is an edge that goes back to the same basic block.)

A basic block in the cycle that can be reached from the entry of the function along a path that does not visit any other basic block in the cycle is called an entry of the cycle. A cycle can have multiple entries.

In any depth-first search starting from the entry of the function, the first node of a cycle to be visited will be one of the entries. This entry is called the header of the cycle. (Informational note — Thus, the header of the cycle is implementation-defined.)

In any depth-first search starting from the entry, set of outermost cycles found in the CFG is the same. These are the top-level cycles that do not themselves have a parent.

The cycles nested inside a cycle C with header H are the outermost cycles in the subgraph induced on the set of nodes (C - H). C is said to be the parent of these cycles, and each of these cycles is a child of C.

Thus, cycles form an implementation-defined forest where each cycle C is the parent of any outermost cycles nested inside C. The tree closely follows the nesting of loops in the same function. The unique entry of a reducible cycle (an LLVM loop) L dominates all its other nodes, and is always chosen as the header of some cycle C regardless of the DFS tree used. This cycle C is a superset of the loop L. For an irreducible cycle, no one entry dominates the nodes of the cycle. One of the entries is chosen as header of the cycle, in an implementation-defined way.

A cycle is irreducible if it has multiple entries and it is reducible otherwise.

A cycle C is said to be the parent of a basic block B if B occurs in C but not in any child cycle of C. Then B is also said to be a child of cycle C.

A basic block or cycle X is a sibling of another basic block or cycle Y if they both have no parent or both have the same parent.

Informational notes:

Non-header entry blocks of a cycle can be contained in child cycles.

If the CFG is reducible, the cycles are exactly the natural loops and every cycle has exactly one entry block.

Cycles are well-nested (by definition).

The entry blocks of a cycle are siblings in the dominator tree.

- HavlakCycles

Paul Havlak, “Nesting of reducible and irreducible loops.” ACM Transactions on Programming Languages and Systems (TOPLAS) 19.4 (1997): 557-567.

Examples of Cycles¶

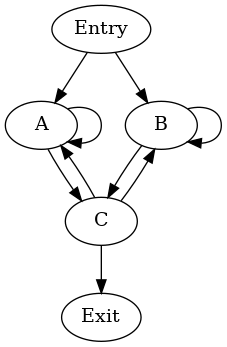

Irreducible cycle enclosing natural loops¶

The self-loops of A and B give rise to two single-block

natural loops. A possible hierarchy of cycles is:

cycle: {A, B, C} entries: {A, B} header: A

- cycle: {B, C} entries: {B, C} header: C

- cycle: {B} entries: {B} header: B

This hierarchy arises when DFS visits the blocks in the order A,

C, B (in preorder).

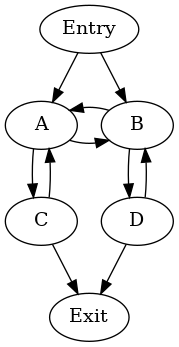

Irreducible union of two natural loops¶

There are two natural loops: {A, C} and {B, D}. A possible

hierarchy of cycles is:

cycle: {A, B, C, D} entries: {A, B} header: A

- cycle: {B, D} entries: {B} header: B

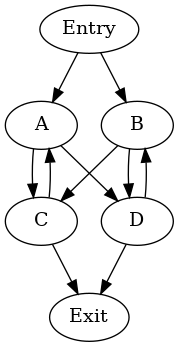

Irreducible cycle without natural loops¶

This graph does not contain any natural loops — the nodes A,

B, C and D are siblings in the dominator tree. A possible

hierarchy of cycles is:

cycle: {A, B, C, D} entries: {A, B} header: A

- cycle: {B, D} entries: {B, D} header: D

Closed Paths and Cycles¶

A closed path in a CFG is a connected sequence of nodes and edges in the CFG whose start and end points are the same.

If a node D dominates one or more nodes in a closed path P and P does not contain D, then D dominates every node in P.

Proof: Let U be a node in P that is dominated by D. If there was a node V in P not dominated by D, then U would be reachable from the function entry node via V without passing through D, which contradicts the fact that D dominates U.

If a node D dominates one or more nodes in a closed path P and P does not contain D, then there exists a cycle C that contains P but not D.

Proof: From the above property, D dominates all the nodes in P. For any nesting of cycles discovered by the implementation-defined DFS, consider the smallest cycle C which contains P. For the sake of contradiction, assume that D is in C. Then the header H of C cannot be in P, since the header of a cycle cannot be dominated by any other node in the cycle. Thus, P is in the set (C-H), and there must be a smaller cycle C’ in C which also contains P, but that contradicts how we chose C.

If a closed path P contains nodes U1 and U2 but not their dominators D1 and D2 respectively, then there exists a cycle C that contains U1 and U2 but neither of D1 and D2.

Proof: From the above properties, each D1 and D2 separately dominate every node in P. There exists a cycle C1 (respectively, C2) that contains P but not D1 (respectively, D2). Either C1 and C2 are the same cycle, or one of them is nested inside the other. Hence there is always a cycle that contains U1 and U2 but neither of D1 and D2.